July 11, 2025

Every post-pubertal woman (who has not yet hit menopause) faces the issues of a monthly cycle. Approximately 80% of young women will have cramps that affect some or all of their periods [1]. Monthly hormone fluctuations can also trigger migraines, impact mood, induce nausea, cause bloating and breast tenderness, and even exacerbate seizures for those suffering from epilepsy. Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) is a recognized medical condition, however research out of the University of Toronto suggests that cycles do not greatly influence mood and that the issue of monthly mood changes has too often been used to undermine women’s credibility. This is yet another area where research is severely lagging. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that PMS prevalence ranged dramatically affecting as little as 12% to as much as 98% of women depending on the study and location [2] . This kind of wide variability highlights the heterogeneity of the condition and is indicative of the need for further research. At the time of this writing, a pubmed search for “premenstrual syndrome” returned just 5,561articles, while a search for “erectile dysfunction” returned 30,956 results.

Dysmenorrhea, or severe and frequent cramps and pain, can be debilitating, yet treatment options are still limited to hormone therapy (including birth-control pills and IUDs) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. Even then, medical professionals often don’t understand the underlying biological mechanisms: for example, many doctors don’t direct their patients to take naproxen BEFORE cramps start, as it is more effective than taking it after they kick in (it has to do with blocking prostaglandin release). Importantly, frequent severe cramps and heavy bleeding are often a sign of endometriosis, yet, as we discuss below, too many family practitioners overlook this possibility and tell young women that their excruciating period pain is “normal”. Another often overlooked aspect of having a monthly period is that an estimated 40% of young women suffer from iron deficiency, and this shocking rate of anemia suggests a significant lack of diagnostic screening for menstrual-related blood loss.

Even menstrual products are affected by male-dominated research. Historically, male researchers used saline to test and rate absorbency, instead of fluids that accurately mimic menstrual blood’s viscosity and consistency. A 2024 study using expired human blood revealed that some pads labeled for heavy flow actually held more than twice their rated capacity [3]. This discrepancy could potentially lead to misdiagnosis of bleeding disorders, as doctors rely on these published metrics to define heavy flow. Furthermore, the problem extends to newer products like menstrual discs and cups, for which no standardized metrics for heavy flow exist. These findings highlight the critical need for more accurate, women-centered research in reproductive health and improved evidence-based education for family physicians.

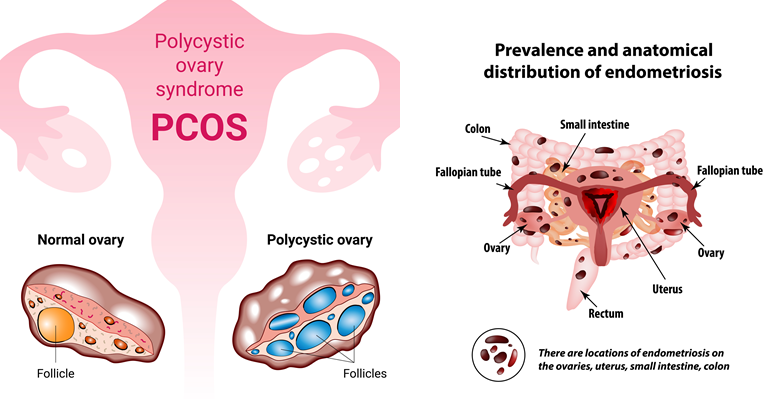

Endometriosis, which affects up to 1 million women in Canada, exemplifies the challenges in women’s healthcare. It can take up to 11 years from the onset of symptoms to receive a proper diagnosis, with many women being told their debilitating pain is normal or psychological [4]. In the UK it affects up to 1 in 10 women, is more common than asthma or diabetes, and takes an average of 9 years, and up to 10 doctors appointments for a woman to obtain a diagnosis [5]. Combined with chronic pain, endometriosis can spread to surrounding organs and tissues. With the risk of bladder and bowel dysfunction and the fact that endometriosis can lead to fertility issues, this delay in diagnosis can have devastating consequences.

Pathological features of PCOS and endometriosis. (Source: depositphotos.com)

In a candid interview with Dr. Mary Alice Haney and Dr. Thaïs Aliabadi, the recording artist Halsey noted that early diagnosis and treatment of her endometriosis was instrumental in being able to conceive her son without IVF. Validating her experience, research from the university of Queensland found that 40% of women diagnosed with endometriosis required IVF to conceive, and those who were diagnosed late went through more rounds and were 33% less likely to get pregnant. There is hope on the horizon, however. The Ainsworth family recently donated $50M AUD to establish the Ainsworth Endometriosis Research Institute (AERI) at the University of New South Wales. Dr. Jen Gunter was instrumental in instigating this boost in research funding, and you can read about it in her fantastic substack article.

Similarly, PCOS patients often face years of delayed diagnosis, with 34% waiting more than two years and 41% seeing three or more doctors before receiving answers.[6] The impact of PCOS extends far beyond fertility issues. More than half of women with PCOS will develop diabetes before age 40, and they face a greatly increased risk of heart disease and endometrial cancer. Additionally, those with PCOS are more susceptible to contracting COVID-19, including an increased risk of severe complications and morbidity [7].

As women age, they also face enormous barriers in addressing the symptoms of menopause and hormone imbalances. In addition to the stigma, there is a pervasive belief that this is a part of normal ageing both inside and outside of the medical community. The 2002 Women’s Health Initiative study findings overstated hormone replacement therapy (HRT) risks for breast cancer and heart attack, casting a long shadow over women’s health. This much-debated study led to widespread misconceptions that created a lasting stain on HRT [8-9]. As a result, many healthcare providers are hesitant to prescribe effective hormone replacement therapy and countless women remain unnecessarily afraid of its benefits [10]. Importantly, route of administration matters: several recent studies and reviews have concluded that transdermal estrogen does not increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), cardiovascular disease, hypertension or heart attack (and may even reduce risk), if started within 10 years of menopause, and before the age of 60 [11-14].

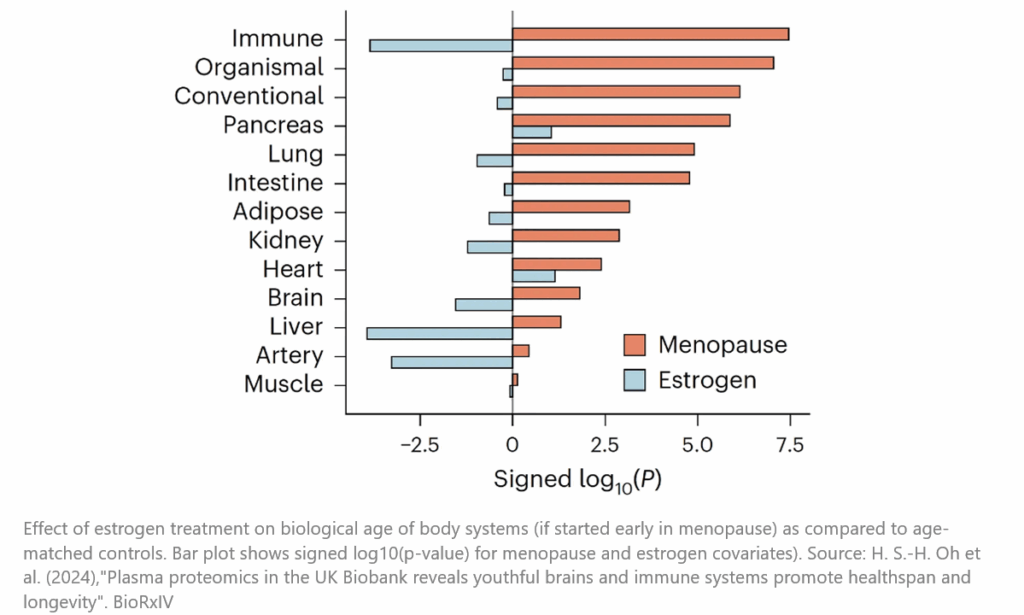

In fact, recent research (still in preprint) has revealed that estrogen replacement, especially when initiated early after menopause, is associated with reduced all-cause mortality, slower aging of key organs, and reduced risk of certain cancers [15]. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the different types of hormone therapies and their timing, including the substantial health benefits women have missed due to outdated misconceptions.

But practitioners are slow to change, and women are suffering needlessly as a result. In a recent UK study, they determined that despite 77% of women experiencing very challenging symptoms that could be addressed by hormone replacement, only 40% of those seeking medical help were offered HRT [10]. Similarly, Dr. Rachael Rubin, a urologist and member of the Menopause Advocacy Working Group, has highlighted that misinformation in the “boxed warning” on vaginal estrogen suppositories has created a false fear in both patients and practitioners of a treatment that can reduce urinary incontinence, reduce pain during sex, stave off vaginal atrophy and prevent urinary tract infections (which can be deadly in the elderly).

Menopause is yet another area that has been grossly underserved in the research community, which is ironic as every woman will go through menopause, and the potential financial benefit alone of meeting the needs of this underserved market should be spurring research. Beyond hot flashes, osteoporosis and the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, many primary care physicians are unaware of the full range of menopausal symptoms including brain fog, joint pain, muscular pain and frozen shoulder, changes in hair growth/loss, loss of libido, tinnitus, dry skin, insomnia, fatigue, recurrent UTIs, and urinary incontinence, to name just a few.

On the positive side, companies like Pfizer, Theramex, Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi, Novartis and Astellas Pharma are all working on, or have released treatments to address some menopausal symptoms and/or osteoporosis*. Pfizer’s (relatively new) HRT product Duavive®/Duavee®, is a combination of estrogens conjugated with bazedoxifene with demonstrated efficacy in reducing hot flashes and osteoporosis in menopausal women [10-12] Bazedoxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that antagonizes estrogen receptors in breast and uterine tissue, negating the need for concomitant progesterone therapy (which many women find problematic). Beyond its role in treating menopausal symptoms, recent research suggests Duavee® treatment may also reduce the risk of developing invasive breast cancer in at-risk post-menopausal women [19]. Issues with the WHI study have left many women and their practitioners leery of HRT to treat menopausal symptoms, so it’s great to see that Astellas Pharma has obtained both FDA and Health Canada approval for VEOZAH®, a non-hormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes). While these advances bring hope, we need to translate these findings into better physician and patient education materials.

These unique challenges underscore the urgent need for more inclusive research and clinical practices tailored specifically to women’s health. From conditions like PCOS and endometriosis to the lost decades in mismanagement of menopause, gaps in understanding and lack of effective therapies continue to impact billions of women worldwide. From a therapeutic perspective, women just want it acknowledged that much of their suffering is not “normal”, and to fully participate in their treatment plans. This is a huge and potentially lucrative untapped market just begging for recognition and better treatment options.

In our next installment (Part B of Chapter 5, “It’s a Girl Thing”), we continue the discussion on health challenges unique to women, including the increased burden of autoimmune disorders, the slow pace of progress in maternal health and postpartum care, and the father’s contribution to pregnancy outcomes. Stay tuned!

*Disclaimer: The mention of specific companies, products, or organizations in this article is for informational purposes only and does not imply endorsement. The companies referenced were not consulted, involved in the preparation of this content, nor did they provide any funding or compensation.

References

[1] G. Grandi et al., “Prevalence of menstrual pain in young women: what is dysmenorrhea?,” J. Pain Res., vol. 5, pp. 169–174, 2012, doi: 10.2147/JPR.S30602.

[2] D.-M. A, S. K, D. A, and K. Sattar, “Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study.,” J. Clin. Diagn. Res., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 106–109, Feb. 2014, doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8024.4021.

[3] E. DeLoughery, A. C. Colwill, A. Edelman, and B. Samuelson Bannow, “Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding,” BMJ Sex. & Reprod. Heal., vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 21 LP – 26, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2023-201895.

[4] C. Allaire, M. A. Bedaiwy, and P. J. Yong, “Diagnosis and management of endometriosis,” Can. Med. Assoc. J., vol. 195, no. 10, p. E363 LP-E371, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1503/cmaj.220637.

[5] “‘Dismissed, ignored and belittled’ The long road to endometriosis diagnosis in the UK,” 2024.

[6] M. Ismayilova and S. Yaya, “‘I felt like she didn’t take me seriously’: a multi-methods study examining patient satisfaction and experiences with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in Canada.,” BMC Womens. Health, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 47, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01630-3.

[7] S. F. de Medeiros, M. M. W. Yamamoto, M. A. S. de Medeiros, A. K. L. W. Yamamoto, and B. B. Barbosa, “Polycystic ovary syndrome and risks for COVID-19 infection: A comprehensive review : PCOS and COVID-19 relationship.,” Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 251–264, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11154-022-09715-y.

[8] L. Vogel, “Trial overstated HRT risk for younger women.,” C. Can. Med. Assoc. J. = J. l’Association medicale Can., vol. 189, no. 17, pp. E648–E649, May 2017, doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095421.

[9] A. Z. Bluming, H. N. Hodis, and R. D. Langer, “’Tis but a scratch: a critical review of the Women’s Health Initiative evidence associating menopausal hormone therapy with the risk of breast cancer.,” Menopause, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1241–1245, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002267.

[10] K. Barber and A. Charles, “Barriers to Accessing Effective Treatment and Support for Menopausal Symptoms: A Qualitative Study Capturing the Behaviours, Beliefs and Experiences of Key Stakeholders.,” Patient Prefer. Adherence, vol. 17, pp. 2971–2980, 2023, doi: 10.2147/PPA.S430203.

[11] Y. Vinogradova, C. Coupland, and J. Hippisley-Cox, “Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases.,” BMJ, vol. 364, p. k4810, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4810.

[12] M. Canonico et al., “Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study.,” Circulation, vol. 115, no. 7, pp. 840–845, Feb. 2007, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642280.

[13] A. Mukherjee and S. R. Davis, “Update on Menopause Hormone Therapy; Current Indications and Unanswered Questions.,” Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf)., Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1111/cen.15211.

[14] P. Bezwada, A. Shaikh, and D. Misra, “The Effect of Transdermal Estrogen Patch Use on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review.,” J. Womens. Health (Larchmt)., vol. 26, no. 12, pp. 1319–1325, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6151.

[15] H. S.-H. Oh et al., “Plasma proteomics in the UK Biobank reveals youthful brains and immune systems promote healthspan and longevity.,” bioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol., Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1101/2024.06.07.597771.

[16] D. F. Archer et al., “Pooled Analysis of the Effects of Conjugated Estrogens/Bazedoxifene on Vasomotor Symptoms in the Selective Estrogens, Menopause, and Response to Therapy Trials.,” J. Womens. Health (Larchmt)., vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 1102–1111, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5558.

[17] S. Mirkin et al., “Gynecologic Safety of Conjugated Estrogens Plus Bazedoxifene: Pooled Analysis of Five Phase 3 Trials.,” J. Womens. Health (Larchmt)., vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 431–442, May 2016, doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5351.

[18] T. J. Beck et al., “The effects of bazedoxifene on bone structural strength evaluated by hip structure analysis.,” Bone, vol. 77, pp. 115–119, Aug. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.027.

[19] S. Kulkarni et al., “The Promise study: A presurgical randomized clinical trial of CE/BZA vs placebo in postmenopausal women with ductal carcinoma in situ.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 43, no. 16_suppl, p. 512, May 2025, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2025.43.16_suppl.512.