December 3, 2025

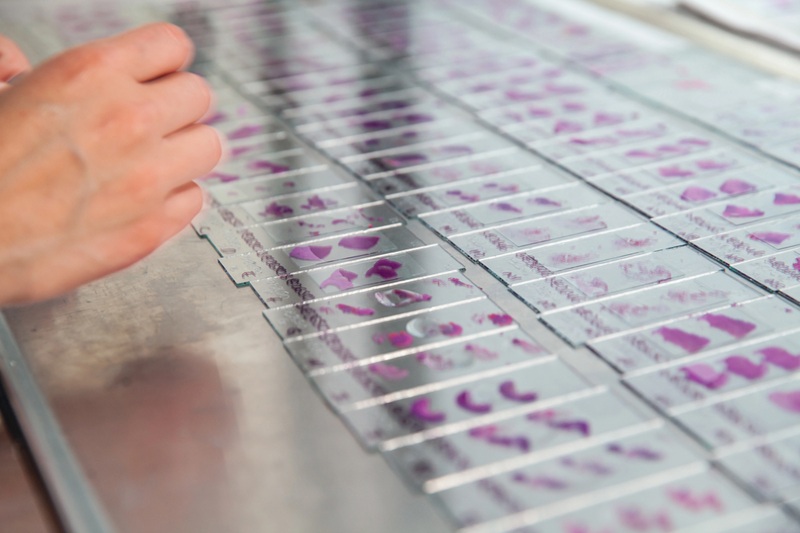

Biopsies have long been the gold standard diagnostic tool in medicine, a trusted window into the body’s most guarded secrets. For more than a century, the formula has barely changed: take a piece of tissue, place it on a slide, stain it, and rely on a pathologist’s expert eye to decode what’s really happening inside. It’s a process that has saved lives, guided therapies, and allowed clinicians to not just diagnose disease, but truly understand it.

But medicine is undergoing a seismic shift, that once-static snapshot is evolving into something far more powerful. Today’s biopsies are becoming dynamic molecular intelligence systems, capturing real-time clues about how disease emerges, adapts, and responds to treatment, sometimes months before a tumor appears on a scan or symptoms ever surface. They are no longer just physical samples they are data, rich with signals that can be analyzed, tracked, and predicted.

As we usher in this new era, diagnostics are evolving into tools that are less invasive, more intelligent, and inherently personalized. The future of biopsies will hinge not on how much tissue we remove, but on how much knowledge we can extract from every sample.

The idea of examining tissue isn’t new, Egyptian and Greek physicians described studying tumors as early as 3000 BCE. However, the modern biopsy didn’t emerge until the early 19th century, coinciding with the invention of the microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the 1670s, which allowed for detailed cellular analysis.

The first true biopsy procedures appeared in the 1800s, involving invasive surgical excisions of large tissue samples that enabled pathologists to visualize disease under magnification for the first time. The term “biopsy” itself was coined in 1879 by French dermatologist Ernest Besnier, from the Greek bios (life) and opsis (sight), literally meaning “view of life” [1]. A pivotal milestone came in 1883 when German physician Paul Ehrlich performed the first percutaneous (non-incision) liver biopsy, using a needle to extract samples without full surgery. The development of techniques such as fine-needle aspiration and core-needle biopsy throughout the 20th century gradually reduced the need for exploratory surgery, especially as ultrasound, CT, and later MRI improved targeting accuracy [2-3].

Despite these advances, tissue biopsies remain invasive. Complications from lung procedures can still happen, including pain, bleeding, and air leaking around the lung (pneumothorax, which can cause the lung to partially collapse). Sometimes the samples taken may miss the most aggressive parts of a tumor because the cancer tissue can be highly variable from one area to another [4]. These limitations inspire an urgent question: can physicians gather deeper insights without relying on invasive procedures?

Liquid biopsy represents one of the most transformative developments in modern oncology. Liquid biopsy analyzes tumor-derived biomarkers in blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), including circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cell-free DNA (ctDNA), and extracellular vesicles (EVs), without needles piercing tissue. Its roots trace to the discovery of CTCs in the late 1860s [5], but 2024–2025 saw major breakthroughs in cancer detection and management through liquid biopsies [6]. By analyzing tumor-derived material, clinicians can identify mutations, detect minimal residual disease (residual cancer cells that could result in recurrence), and monitor treatment response with greater sensitivity than imaging alone [6]. Studies in non-small cell lung cancer demonstrate that circulating tumor DNA can identify actionable genetic biomarkers, such as EGFR and ALK alterations, enabling targeted therapy even when tissue biopsies are infeasible [7,8].

For many patients today, the first biopsy is no longer a needle, it is a routine blood draw.

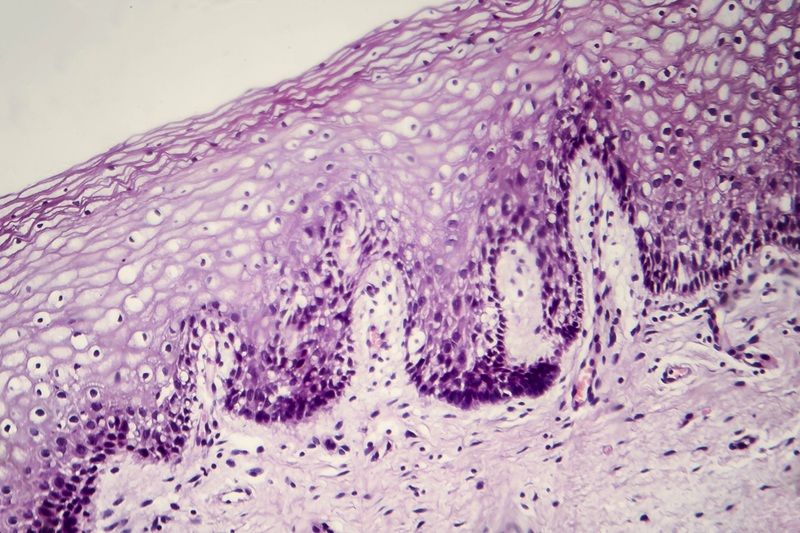

Artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping how biopsy data is interpreted. By analyzing standard hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) stained slides that are already generated in everyday practice, high-performance algorithms can grade tumors, quantify immune cell infiltration, and even predict molecular mutations, without requiring any additional specialized staining or new biopsy techniques [9].

Multicenter evaluations and meta‑analyses show that AI‑assisted imaging workflows can reduce review time by up to about 40% without sacrificing accuracy. Rather than replacing pathologists, these systems expand their reach, transforming static images into actionable, quantitative information that helps refine treatment decisions [10,11].

Spatial transcriptomics and multiplexed proteomic imaging extend traditional histology by overlaying high‑dimensional molecular data onto intact tissue architecture, largely enabled by the rapid maturation of single‑cell RNA sequencing. These approaches allow researchers to localize gene and protein expression at (or near) single‑cell and micrometer resolution, revealing how malignant, immune, and stromal cells are organized and interact within the tumor microenvironment [12-15].

By mapping gene and protein expression in situ, these technologies effectively turn a biopsy from a static two‑dimensional snapshot into a spatially resolved, 3D functional atlas that reports what different cell types are present, how they are organized, and which signaling programs they engage. This integrated view of structure and function provides a more mechanistic “story” of tissue biology that can guide biomarker discovery and refine therapeutic decision‑making in oncology and beyond [12,14,16,17].

One of the most exciting new strategies in diagnostic science involves synthetic biomarkers. Tumors in their earliest stages may release too few natural markers to detect. Nanoparticles designed to interact with specific cancer-related enzymes can amplify otherwise undetectable signals and release measurable barcodes into blood or urine [18,19].

While these approaches remain largely preclinical, early work suggests the possibility of highly sensitive, inexpensive detection methods, even for early or hidden malignancies. This technology represents an essential step toward pre-symptomatic diagnosis.

Lung cancer remains the deadliest cancer worldwide in part because small outer lung nodules are hard to biopsy safely and accurately. Robotic bronchoscopy, paired with AI-driven navigation, significantly improves access to these areas, reaching lesions historically beyond the capability of conventional scopes. Moreover, this technique results in reduced complications and improved diagnostic yield, especially in early-stage disease [20, 21].

The future of biopsy is defined by its integration into continuous, personalized monitoring. Instead of a single diagnostic event, clinicians will be able to follow molecular changes over time. Minimal residual disease detection through circulating tumor DNA can often identify relapse months before it appears on imaging, providing a critical window for intervention.

To meet the needs of precision medicine, a diagnostic ecosystem is emerging. Tissue biopsies provide histology and spatial context. Liquid biopsies supply real-time molecular readouts. Synthetic biomarkers may one day reveal disease even before tumors form visible structures. AI connects these data streams into clinically actionable analytics.

Biopsy, in other words, is becoming less of a procedure and more of a platform.

From early surgical extractions to smart nanoparticle diagnostics, the trajectory of biopsy innovation points toward earlier detection, fewer complications, and a more comprehensive understanding of disease. The next era of diagnostics will be one in which patients face less pain and anxiety and clinicians know more, where the fear associated with the word “biopsy” fades, replaced by confidence in accurate, timely information.

The core mission of biopsy has never changed: to provide a clear view of life. What has changed is how much more life we can see.

[2] K. P. H. Pritzker and H. J. Nieminen, “Needle Biopsy Adequacy in the Era of Precision Medicine and Value-Based Health Care,” Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med., vol. 143, no. 11, pp. 1399–1415, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.5858/ARPA.2018-0463-RA.

[3] E. Silva, S. Meschter, and M. P. Tan, “Breast biopsy techniques in a global setting—clinical practice review,” Transl. Breast Cancer Res., vol. 4, p. 14, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.21037/TBCR-23-12/PRF.

[4] L. Dalag, J. K. Fergus, and S. M. Zangan, “Lung and Abdominal Biopsies in the Age of Precision Medicine,” Semin. Intervent. Radiol., vol. 36, no. 3, p. 255, 2019, doi: 10.1055/S-0039-1693121.

[5] M. P. Wong, “Circulating tumor cells as lung cancer biomarkers,” J. Thorac. Dis., vol. 4, no. 6, p. 631, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.3978/J.ISSN.2072-1439.2012.10.05.

[6] S. Zhang et al., “Tracing the history of clinical practice of liquid biopsy: a bibliometric analysis,” Front. Immunol., vol. 16, p. 1574736, May 2025, doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2025.1574736/BIBTEX.

[7] M. Mino-Kenudson et al., “Predictive Biomarkers for Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: Perspective From the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology Committee,” J. Thorac. Oncol., vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 1335–1354, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.JTHO.2022.09.109.

[8] A. Isaic et al., “Next-Generation Sequencing: A Review of Its Transformative Impact on Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Resistance Management,” Diagnostics, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 2425, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS15192425.

[9] W. Bulten et al., “Artificial intelligence for diagnosis and Gleason grading of prostate cancer: the PANDA challenge,” Nat. Med., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 154–163, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1038/S41591-021-01620-2.

[10] M. Chen et al., “Impact of human and artificial intelligence collaboration on workload reduction in medical image interpretation,” npj Digit. Med. 2024 71, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 349-, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01328-w.

[11] K. Wenderott, J. Krups, F. Zaruchas, and M. Weigl, “Effects of artificial intelligence implementation on efficiency in medical imaging—a systematic literature review and meta-analysis,” npj Digit. Med. 2024 71, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 265-, Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01248-9.

[12] S. K. Longo, M. G. Guo, A. L. Ji, and P. A. Khavari, “Integrating single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to elucidate intercellular tissue dynamics,” Nat. Rev. Genet., vol. 22, no. 10, p. 627, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1038/S41576-021-00370-8.

[13] M. F. de Oliveira et al., “High-definition spatial transcriptomic profiling of immune cell populations in colorectal cancer,” Nat. Genet., vol. 57, no. 6, p. 1512, Jun. 2025, doi: 10.1038/S41588-025-02193-3.

[14] G. Molla Desta and A. G. Birhanu, “Advancements in single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics: transforming biomedical research,” Acta Biochim. Pol., vol. 72, 2025, doi: 10.3389/ABP.2025.13922/PDF.

[15] B. Hu, M. Sajid, R. Lv, L. Liu, and C. Sun, “A review of spatial profiling technologies for characterizing the tumor microenvironment in immuno-oncology,” Front. Immunol., vol. 13, p. 996721, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.996721/FULL.

[16] Z. Abdulrahman, R. C. Slieker, D. McGuire, M. J. P. Welters, M. I. E. Van Poelgeest, and S. H. Van Der Burg, “Single-cell spatial transcriptomics unravels cell states and ecosystems associated with clinical response to immunotherapy,” J. Immunother. Cancer, vol. 13, no. 3, p. e011308, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1136/JITC-2024-011308.

[17] Y. Li, H. Qiu, Z. Zhao, F. Qi, and P. Cai, “Single-cell technologies and spatial transcriptomics: decoding immune low – response states in endometrial cancer,” Front. Immunol., vol. 16, p. 1636483, Jul. 2025, doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2025.1636483/BIBTEX.

[18] G. A. Kwong et al., “Mass-encoded synthetic biomarkers for multiplexed urinary monitoring of disease,” Nat. Biotechnol., vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 63–70, Jan. 2013, doi: 10.1038/NBT.2464.

[19] L. Hao et al., “CRISPR-Cas-amplified urinary biomarkers for multiplexed and portable cancer diagnostics,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 798–807, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.1038/S41565-023-01372-9;TECHMETA.

[20] J. D. Duke and J. Reisenauer, “Robotic bronchoscopy: potential in diagnosing and treating lung cancer,” Expert Rev. Respir. Med., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 213–221, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1080/17476348.2023.2192929;PAGE:STRING:ARTICLE/CHAPTER.

[21] M. Giri, H. Dai, A. Puri, J. Liao, and S. Guo, “Advancements in navigational bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: A review with special focus on virtual bronchoscopic navigation,” Front. Med., vol. 9, p. 989184, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.3389/FMED.2022.989184/BIBTEX.