September 3, 2025

In our previous article, we reviewed the history of Patient Centered Care and how the Picker Principles provided a foundation for empowering patients and improving healthcare outcomes around the world. We highlighted that patient autonomy is a cornerstone of this approach, yet it is also one of the most challenging areas to effectively navigate. In this article we propose tangible approaches to continuing medical education (CME) that can equip providers with the tools and skills to deliver effective patient-centered care while respecting time constraints in today’s busy healthcare environment.

In our previous article, we reviewed the history of Patient Centered Care and how the Picker Principles provided a foundation for empowering patients and improving healthcare outcomes around the world. We highlighted that patient autonomy is a cornerstone of this approach, yet it is also one of the most challenging areas to effectively navigate. In this article we propose tangible approaches to continuing medical education (CME) that can equip providers with the tools and skills to deliver effective patient-centered care while respecting time constraints in today’s busy healthcare environment.

To move from theory to practice, CME must shift away from traditional, passive learning and toward a new model of skills development. A core principle of this model is “active learning”- an approach that incorporates interactivity, practice and contextual relevance to improve retention and recall in challenging situations. The first and most critical step is to immerse physicians in situations that simulate the challenges they face every day:

Once again, the training should not just be passive reading or reviewing of slides; it must involve principles of “active learning”, including novelty, interactive participation, rehearsal, and self-evaluation to reinforce concepts and the ability to deliver effectively under pressure [13].

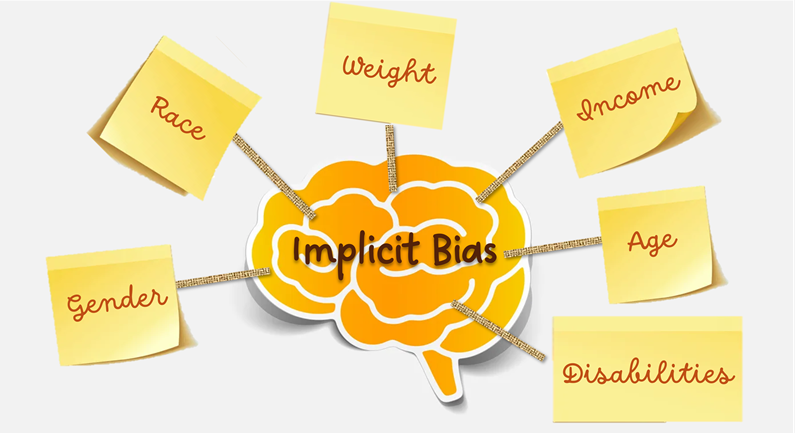

Cultural competence training should include modules that enhance cultural sensitivity and awareness for groups that have traditionally reported significant difficulties in navigating healthcare, including lived experiences from women and individuals from marginalized communities [15-17]. Additionally, implicit biases around appearance, weight, sexual orientation, and gender identity have been found to affect practitioner attitudes and responses to patients [18, 19]. This training should focus on helping practitioners both identify and address their own implicit biases, as ingrained tendencies can impede delivery of optimal care, particularly in high-stakes situations. Because biases are often deeply ingrained, this form of training should be repeated on a regular basis, as one-time delivery of bias training has been found to be ineffective in shifting attitudes and behaviours [20, 21].

By building more effective CME programs, we can bridge the gap between medical expertise and effective patient communication to improve patient outcomes. Training for patient-centered care isn’t about learning new medical facts or how to treat a condition; it must focus on developing, practicing and honing a vital set of soft skills that empower physicians to connect with patients on a human level, even when they face busy schedules and demanding workloads. Indeed, physicians report that one of their biggest impediments to engaging in shared decision making is time constraints. Yet, studies found that consultation durations did not increase when shared decision making was implemented after proper training interventions [10]. This demonstrates that well-designed, targeted training can give physicians the tools to overcome perceived barriers like time constraints and build stronger patient connections.

As we continue to evolve our approach to healthcare education, patient-centered care must be prioritized in every aspect. Honoring the ongoing work of the Picker Institute and the principles they established, we need to keep the patient at the center of everything we do.

References

[2] E. M. Oehrlein et al., “Developing Patient-Centered Real-World Evidence: Emerging Methods Recommendations From a Consensus Process,” Value Heal., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 28–38, 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2022.04.1738.

[3] C. Elendu et al., “The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review.,” Medicine (Baltimore)., vol. 103, no. 27, p. e38813, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000038813.

[4] D. Nestel and T. Tierney, “Role-play for medical students learning about communication: guidelines for maximising benefits.,” BMC Med. Educ., vol. 7, p. 3, Mar. 2007, doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-3.

[5] A. Pilnick, D. Trusson, S. Beeke, R. O’Brien, S. Goldberg, and R. H. Harwood, “Using conversation analysis to inform role play and simulated interaction in communications skills training for healthcare professionals: identifying avenues for further development through a scoping review.,” BMC Med. Educ., vol. 18, no. 1, p. 267, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1381-1.

[6] A. Yamamoto et al., “Enhancing Medical Interview Skills Through AI-Simulated Patient Interactions: Nonrandomized Controlled Trial,” JMIR Med Educ, vol. 10, p. e58753, 2024, doi: 10.2196/58753.

[7] G. Elwyn et al., “Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice.,” J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 1361–1367, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6.

[8] L. Samalin, J.-B. Genty, L. Boyer, J. Lopez-Castroman, M. Abbar, and P.-M. Llorca, “Shared Decision-Making: a Systematic Review Focusing on Mood Disorders.,” Curr. Psychiatry Rep., vol. 20, no. 4, p. 23, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0892-0.

[9] V. Y. Siebinga, E. M. Driever, A. M. Stiggelbout, and P. L. P. Brand, “Shared decision making, patient-centered communication and patient satisfaction – A cross-sectional analysis.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 105, no. 7, pp. 2145–2150, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.03.012.

[10] D. T. Ubbink, F. Shamoun, S. Heuvelsland, F. S. van Etten-Jamaludin, and E. E. Bolt, “To what extent do general practitioners involve patients in decision-making? A systematic review of studies using the OPTION-instrument.,” Prim. Health Care Res. Dev., vol. 26, p. e67, Jul. 2025, doi: 10.1017/S1463423625100303.

[11] R. L. Gundling, “Hearing the Voice of the Patient in Value-Based Care Initiatives: Lessons from International Experiences.,” Front. Health Serv. Manage., vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 10–17, 2025, doi: 10.1097/HAP.0000000000000216.

[12] L. Scott et al., “Exploring a collaborative approach to the involvement of patients, carers and the public in the initial education and training of healthcare professionals: A qualitative study of patient experiences.,” Heal. Expect. an Int. J. public Particip. Heal. care Heal. policy, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1988–1994, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1111/hex.13338.

[13] J. M. Dubinsky and A. A. Hamid, “The neuroscience of active learning and direct instruction,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 163, p. 105737, 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105737.

[14] I. Cruz-Panesso, I. Tanoubi, and P. Drolet, “Telehealth Competencies: Training Physicians for a New Reality?,” Healthc. (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.3390/healthcare12010093.

[15] A. Al Hamid et al., “Gender Bias in Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review.,” Cureus, vol. 16, no. 2, p. e54264, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.7759/cureus.54264.

[16] K. M. Hoffman, S. Trawalter, J. R. Axt, and M. N. Oliver, “Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 113, no. 16, pp. 4296–4301, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

[17] A. Samulowitz, I. Gremyr, E. Eriksson, and G. Hensing, “‘Brave Men’ and ‘Emotional Women’: A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain.,” Pain Res. Manag., vol. 2018, p. 6358624, 2018, doi: 10.1155/2018/6358624.

[18] A. S. Alberga, I. Y. Edache, M. Forhan, and S. Russell-Mayhew, “Weight bias and health care utilization: a scoping review.,” Prim. Health Care Res. Dev., vol. 20, p. e116, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1017/S1463423619000227.

[19] J. N. Fish, R. E. Turpin, N. D. Williams, and B. O. Boekeloo, “Sexual Identity Differences in Access to and Satisfaction With Health Care: Findings From Nationally Representative Data.,” Am. J. Epidemiol., vol. 190, no. 7, pp. 1281–1293, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab012.

[20] C. O. for S. W. D. (COSWD National Institutes of Health (US), Office of the Director (OD), “Is Implicit Bias Training Effective?,” in Scientific Workforce Diversity Seminar Series (SWDSS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603840/

[21] L. A. Cooper, S. Saha, and M. van Ryn, “Mandated Implicit Bias Training for Health Professionals—A Step Toward Equity in Health Care,” JAMA Heal. Forum, vol. 3, no. 8, pp. e223250–e223250, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3250.

[22] D. R. Bridges, R. A. Davidson, P. S. Odegard, I. V Maki, and J. Tomkowiak, “Interprofessional collaboration: three best practice models of interprofessional education.,” Med. Educ. Online, vol. 16, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035.

[23] A. M. Heredia-Rizo, M. J. Casuso-Holgado, and J. Martínez-Calderón, “Editorial: Interprofessional approaches for the management of chronic diseases.,” 2024, Switzerland. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1490575.

[24] G. K. Tippin, K. A. Maranzan, and M. A. Mountain, “Client Outcomes Associated With Interprofessional Care in a Community Mental Health Outpatient Program,” Can. J. Community Ment. Heal., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 83–96, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2016-042.