July 16, 2025

In the USA, after decades of decline, the number of women who die from complications due to pregnancy and childbirth started rising in 2021, with loss of life in black women at 2.6 times the rate of non-Hispanic white women. In Canada, a similar scenario is unfolding, with maternal mortality increasing since 2021, and rising from 8.1 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2021 to 12.22 in 2023. Factors impacting maternal mortality in high-income countries like Canada and the US include increasing maternal age, lack of access to emergency and obstetric care (particularly in rural communities), missing continuity and coordination of post-partum care, and a lack of access to, and options for, preconception care targeting women’s health before pregnancy.

These areas are hindered both by excluding pregnant and lactating women from many clinical trials, but also by a shocking lack of innovative interventions for pregnant and lactating women, and postpartum and preconception care [1]. Navigating the complexities of ensuring a treatment is both safe for mother and baby and effective in treating the targeted condition is incredibly challenging. But it can be done, as was demonstrated by the work that ensured pravastatin was safe and effective for treating high-risk pregnant women with a history of preeclampsia [1]. Unfortunately, for many common and serious pregnancy-related conditions, clinical practice has remained unchanged for decades, leaving families and physicians with outdated protocols and limited options.

Being parents, especially first-time parents, is scary enough without being faced with medical uncertainties and difficult, no-win decisions. Since the 1990’s many countries have been testing pregnant mothers for Group B Strep (GBS). Somewhere between 20-40% of pregnant women carry it at any given time, but the chances of infecting their child with GBS syndrome are 1-2%. Of those babies infected, ten percent or less can have severe outcomes, including death. The standard of care for women who test positive in high-income nations has not changed since the 1990s – it is IV-antibiotic treatment during labor, given every 4 hours.

However, this treatment is not without consequences. The impact of being administered a massive dose of antibiotics, possibly unnecessarily, damages the mother’s microbiome, destroying most of the helpful bacteria in the birth canal. These bacteria are essential to establishing the baby’s early immune system [2]. If the baby cannot be breastfed, the adverse impacts on the development of their microbiota can persist for at least 1 year [2], with no data for the long-term impacts on antibiotic resistance and immune function. Importantly, antibiotics given during birth cannot prevent GBS-related stillbirths (global estimate of 150,00/yr), late-onset GBS disease in infants, and don’t even guarantee the prevention of early-onset GBS (in ~30% of cases where mothers received IV antibiotics) [3]. GBS vaccines are under development (thanks to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Pfizer), but progress has been slow – it’s been over 30 years since we discovered the impact of GBS on infant mortality, and we still don’t have a vaccine available.

Childbirth and postpartum care are another set of areas overlooked in both research and supportive care innovations. Most postpartum care focuses on the child, yet between 47% to 94% of women report having both physical and mental health issues in the first year after childbirth, with some of those issues, like incontinence, persisting for years [4]. A recent series on maternal health published in the Lancet, highlighted that while 1 in 3 women experience complications after childbirth, recognition and treatment of postpartum complications have been largely neglected in clinical research and public policy [5]. Indeed, two separate clinical trials,18 years apart, concluded that many postpartum concerns had not changed much, with recovery pain, feeding issues and difficulty obtaining governmental assistance prominent in both trials [6]. Sadly, the standard of early postpartum care on the pain front hasn’t significantly moved beyond NSAIDs (acetaminophen/ibuprofen), squeeze bottles and sitz baths – a treatment that hasn’t been updated in over 50 years.

Postpartum mental health is another area where support is lagging. Long minimized by terms like “the baby blues”, postpartum depression is finally garnering attention, but there is still a dearth of good treatment options, as many nursing mothers do not want to take medications that might affect their infants. In addition to hormonal changes, sleep deprivation is a primary driver of postpartum depression, which, if left untreated, can escalate into psychosis with devastating consequences.

Ironically, prescribing sleep for the mother can profoundly improve outcomes [7]; yet, implementation often fails due to a combination of societal expectations, socioeconomic factors, and lack of trained medical professionals who can deliver the specialized interventions that involve changing family dynamics. In Canada, our medical systems can prescribe post-injury or post-surgery in-home care, but prescribing a “night nurse” (a trained professional who helps with nighttime feedings and lactation training, allowing parents to get much-needed sleep) isn’t even an option unless the mother is recovering from surgery complications. Even extended health plans do not cover this service. In the US, some insurance plans will cover the services of a night nurse for a few nights, but most do not.

Did you feel supported before and during pregnancy, birth, and postpartum?

Whether as a patient, parent, or provider, we’d love to hear about your experience. What needs to change in how we approach maternal (and paternal) care? Let us know in the comments on our LinkedIn Post!

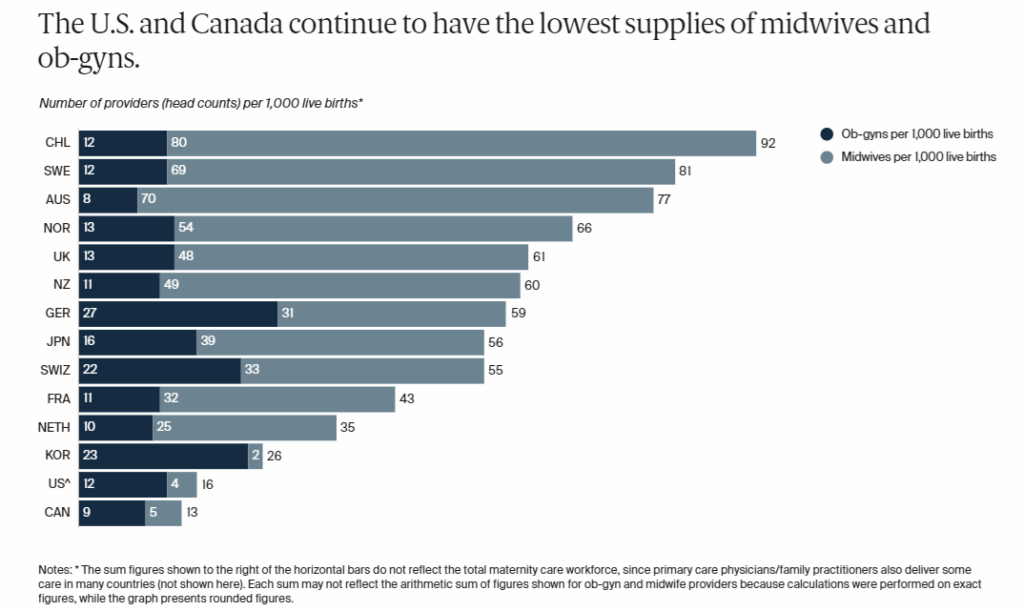

Not only do we need more research into postpartum care, but we also need to address systemic barriers that are driving declining birth rates, like access to prenatal and maternal care and changing demographics. For example, among the high-income countries, the USA and Canada have the fewest number of midwives and obstetricians per 1000 live births. How can we have the highest education rate in the world and yet have the fewest number of birth specialists?

Socioeconomic factors also play a role, with more women starting families later in life. In Canada, the percentage of first-time mothers over the age of 35 has shifted from 10.7% in 1993 to 26.5% in 2023, with a concomitant increase in fertility issues, yet coverage for IVF is not universally available. The US stands alone among the G7 in lacking federally mandated paid maternity leave. Access to affordable childcare is also a huge impediment for most couples considering starting a family. As epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina said of the US system, “If the government wants to be part of the solution, it shouldn’t just throw out incentives. It should invest in the foundation: affordable care, parental leave, safe childbirth, and supportive systems.”

In the realm of pregnancy, maternal health, age, and genetics have been seen as the primary predictors of difficulties during pregnancy and adverse impacts on her children. However, recent research suggests that the father’s health prior to conception plays a much bigger role than previously thought. In 2013, Cornell University scientists determined that it was the father’s genes that were predominantly expressed in the placenta [8], yet very little work has been done to determine how the father’s health might impact their partner’s pregnancy and offspring. What little evidence we have to date indicates that:

These recent studies highlight the legacy of research gaps in preconception care. Clearly, we need to expand research into this interplay to better understand the full impact of paternal health and genetics on maternal health and infant outcomes.

To close these gaps, governments must commit to policy change, and industry must step up with clinical innovations to meet the needs of this underserved community. Increasing the number of trained maternal health providers, expanding access to multidisciplinary postpartum care, and ensuring universal coverage for essential services such as mental health support, paid parental leave, and affordable childcare are crucial steps. Additionally, investing in research on both maternal and paternal preconception health factors, as well as designing interventions to address the unique needs of women, will help create a more equitable and effective healthcare system for all families.

In our next article, we’ll explore the “mental health paradox” in women’s health, examining why, despite increasing dialogue, so many women still struggle to access timely, effective mental health care during some of the most vulnerable periods of their lives.

References

[3] S. A. Nanduri et al., “Epidemiology of Invasive Early-Onset and Late-Onset Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States, 2006 to 2015: Multistate Laboratory and Population-Based Surveillance,” JAMA Pediatr., vol. 173, no. 3, pp. 224–233, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

[4] M. M. Gmelig Meyling, M. E. Frieling, J. P. M. Vervoort, E. I. Feijen-de Jong, and D. E. M. C. Jansen, “Health problems experienced by women during the first year postpartum: A systematic review,” Eur. J. Midwifery, vol. 7, no. December, pp. 1–20, 2023, doi: 10.18332/ejm/173417.

[5] J. P. Vogel et al., “Neglected medium-term and long-term consequences of labour and childbirth: a systematic analysis of the burden, recommended practices, and a way forward,” Lancet Glob. Heal., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. e317–e330, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00454-0.

[6] J. Hannan, D. Brooten, J. M. Youngblut, and A. M. Galindo, “Comparing mothers’ postpartum concerns in two clinical trials 18 years apart.,” J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract., vol. 28, no. 11, pp. 604–611, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12384.

[7] N. Leistikow, E. B. Baller, P. J. Bradshaw, J. N. Riddle, D. A. Ross, and L. M. Osborne, “Prescribing Sleep: An Overlooked Treatment for Postpartum Depression.,” Biol. Psychiatry, vol. 92, no. 3, pp. e13–e15, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.03.006.

[8] X. Wang, D. C. Miller, R. Harman, D. F. Antczak, and A. G. Clark, “Paternally expressed genes predominate in the placenta.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 110, no. 26, pp. 10705–10710, Jun. 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308998110.

[9] J. T. Rumph et al., “A Preconception Paternal Fish Oil Diet Prevents Toxicant-Driven New Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Neonatal Mice.,” Toxics, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.3390/toxics10010007.

[10] K. L. Bruner-Tran, T. Ding, K. B. Yeoman, A. Archibong, J. A. Arosh, and K. G. Osteen, “Developmental exposure of mice to dioxin promotes transgenerational testicular inflammation and an increased risk of preterm birth in unexposed mating partners.,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e105084, 2014, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105084.

[11] R. S. da Cruz, E. Chen, M. Smith, J. Bates, and S. de Assis, “Diet and Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Breast Cancer: The Role of the Paternal Germline.,” Front. Nutr., vol. 7, p. 93, 2020, doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00093.

[12] E. Innocenzi et al., “Paternal activation of CB(2) cannabinoid receptor impairs placental and embryonic growth via an epigenetic mechanism.,” Sci. Rep., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 17034, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53579-3.

[13] C. Galaviz-Hernandez, M. Sosa-Macias, E. Teran, J. E. Garcia-Ortiz, and B. P. Lazalde-Ramos, “Paternal Determinants in Preeclampsia.,” Front. Physiol., vol. 9, p. 1870, 2018, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01870.

[14] J. Lin, W. Gu, and H. Huang, “Effects of Paternal Obesity on Fetal Development and Pregnancy Complications: A Prospective Clinical Cohort Study.,” Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)., vol. 13, p. 826665, 2022, doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.826665.

[15] A. M. Kasman, C. A. Zhang, S. Li, D. K. Stevenson, G. M. Shaw, and M. L. Eisenberg, “Association of preconception paternal health on perinatal outcomes: analysis of U.S. claims data,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 113, no. 5, pp. 947–954, May 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.12.026.

[16] T. Carter, D. Schoenaker, J. Adams, and A. Steel, “Paternal preconception modifiable risk factors for adverse pregnancy and offspring outcomes: a review of contemporary evidence from observational studies,” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 509, 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15335-1.