July 23, 2025

As we continue our series on The Care Gap – Rethinking Women’s Health in Medicine, this sixth installment focuses on mental health − an area with complex disparities. While women seek professional help for depression at twice the rate of men, gender biases in diagnosis and treatment have disadvantaged both men and women.

In the mental health arena, gender plays a complicated and often contradictory role: Women are diagnosed with depression and anxiety at roughly twice the rate of men, yet some experts argue this disparity may reflect preconceptions and biases in how we perceive and diagnose these conditions rather than a true difference in prevalence [1].

Cultural norms often discourage men from seeking help for mental health issues, leading to potentially grave consequences. The male suicide rate is 3.8 times that of women, and men exhibit higher rates of substance use, risk-taking behaviors, and aggression – all of which may be maladaptive coping mechanisms [2]. A US-based national survey found that 9% of men reported symptoms of depression, yet less than half sought treatment, suggesting a significant underdiagnosis of depression in men rather than a genuinely higher prevalence in women [1]. A huge meta-analysis of data from 90 different nations determined that the odds of women being diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) were almost twice that of men, yet the difference between men and women in terms of depressive symptoms was small [3].

Beyond our biology, socioeconomic factors such as income inequality, discrimination and victimization may also contribute to the prevalence of female depression [4]. Women’s salaries in the US are, on average, 83.7% of men’s, and research has shown that women who earn less than their male counterparts face nearly 2.5 times higher odds of depression and four times higher odds of anxiety compared to men with similar qualifications and roles [5]. This disparity suggests that pay and structural inequities in the workforce play a significant role in women’s mental health.

While women should be commended for their greater willingness to seek treatment for mental health issues, it inadvertently creates a bias among healthcare providers. This bias can lead to the misattribution of legitimate physiological complaints to mental health issues, potentially delaying proper diagnosis and treatment of underlying physical conditions. Implicit bias plays a part. In a diagnostic test where physicians watched videos of men and women describing the same cardiovascular disease symptoms, women were twice as likely to be diagnosed with a mental health condition [6]!

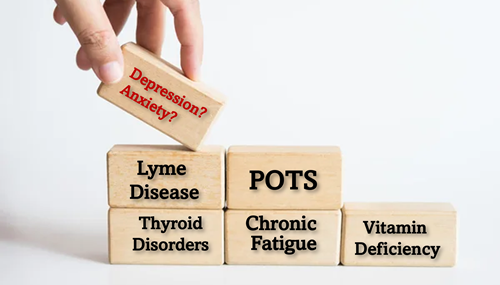

Whether women are more susceptible to depression or not, the fact that they seek treatment twice as often as men, combined with symptoms that often mirror other conditions, has led many physicians to focus on a depression diagnosis in women while overlooking other possible causes. Consider the young mother who sought help from her family doctor for debilitating fatigue, and instead of running tests or even doing a physical exam, he suggested a prescription for antidepressants. This diagnosis completely dismissed her swollen glands, and only after she insisted on further diagnostics did they discover that she had mononucleosis. Sadly, this story is not unique – many conditions that are more prevalent in women have symptom overlap that can be mistaken for mental health disorders:

And where depression is co-morbid with physiological disease in women, many physicians tend to focus solely on the patient’s mental health. Ironically (and tragically), women suffering from MDD are more likely than men with MDD to have serious comorbid conditions like cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [12].

The language used in mental health diagnoses further perpetuates the gender bias. Depression symptoms classified as “typical” are based on diagnostic criteria derived from male-based research, yet women are four times more likely to receive an “atypical” diagnosis [13]. While this distinction may be well-understood by psychologists and psychiatrists, up to 60% of antidepressants are prescribed by a family doctor, yet the most significant gaps in effective treatment stem from primary care [14]. These gaps can include missed diagnoses, inadequate dosage, and inappropriate treatment strategies, highlighting the need for better continuing medical education and collaborative care models that involve community-based mental health professionals in treatment plans.

Despite conflicting studies on the impact of sex in treatment, it appears that, in general, young women tend to respond better to SSRI antidepressant treatments, whereas men may respond better to tricyclic antidepressants. The impact of antidepressant side-effects also differs by sex, with women disproportionately affected by and more likely to discontinue SSRI treatment due to weight gain [15]. Similarly, drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics can differ by sex, genetics and drug, impacting drug clearance and dosage requirements [16]. This is yet another area where significantly more research is required to adequately map sex-specific differences to support effective personalized treatment plans.

Pharmacogenomic testing (PGx) analyzes genes for drug metabolism and side-effect risks, providing for optimized treatment of psychiatric conditions. PGx is now available in many jurisdictions, and despite an estimated cost savings of $3000 per patient, and improved treatment outcomes [17], public health systems in Canada and the US do not cover this diagnostic test. Even if paid out-of-pocket, patients often struggle to get doctors to use PGx results, as many prescribers feel they lack the training to properly implement genetic testing into their practice [18].

Ultimately, we face an efficacy issue when it comes to treating depression, with SSRIs taking 8 to 12 weeks to “work” (classified as a 50% reduction in symptoms), and an estimated 30% of individuals with MDD failing to respond to at least 2 different antidepressants [19]. Not surprisingly, women make up a disproportionate number of those classified as “treatment resistant”.

We are suffering from a global mental health crisis, and we urgently need systemic change when it comes to diagnosing and treating mental health disorders in both men and women. The cost is enormous both in terms of personal and financial impacts, with the economic burden in 2019 estimated to be over $300B in the US alone [20]. We need better, faster-acting antidepressants with fewer side-effects, and we need to ensure they are tested on and work for women as well as men.

We are suffering from a global mental health crisis, and we urgently need systemic change when it comes to diagnosing and treating mental health disorders in both men and women. The cost is enormous both in terms of personal and financial impacts, with the economic burden in 2019 estimated to be over $300B in the US alone [20]. We need better, faster-acting antidepressants with fewer side-effects, and we need to ensure they are tested on and work for women as well as men.

Training doctors to look beyond mental health when treating female patients and fostering a culture that prioritizes listening, validating their concerns, and treating them as true partners in their treatment plans is essential.  Enhanced research into sex-specific pharmacokinetics and timely dissemination of that information to primary care providers is also essential to bridging this gap. We need to incorporate PGx into more randomized clinical trials for different psychiatric disorders [18], and include compulsory continuing medical education training that targets understanding and interpreting pharmacogenomics.

Enhanced research into sex-specific pharmacokinetics and timely dissemination of that information to primary care providers is also essential to bridging this gap. We need to incorporate PGx into more randomized clinical trials for different psychiatric disorders [18], and include compulsory continuing medical education training that targets understanding and interpreting pharmacogenomics.

Closing the gaps in research and medical education will not only drive more inclusive research but also empower the primary care physicians to better distinguish between physical and mental health issues. These types of policy and training changes are necessary if we want to deliver personalized medicine that significantly improves mental and physical health outcomes for both men and women.

In our final article, we will discuss barriers to women’s success in medicine and research and propose solutions and systemic changes necessary to close the gaps and enable a future that provides truly equitable care. Stay tuned!

References

[1] K. M. Sileo and T. S. Kershaw, “Dimensions of Masculine Norms, Depression, and Mental Health Service Utilization: Results From a Prospective Cohort Study Among Emerging Adult Men in the United States,” Am. J. Mens. Health, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 1557988320906980, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1177/1557988320906980.[2] A. B. Rochlen, D. A. Paterniti, R. M. Epstein, P. Duberstein, L. Willeford, and R. L. Kravitz, “Barriers in diagnosing and treating men with depression: a focus group report.,” Am. J. Mens. Health, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 167–175, Jun. 2010, doi: 10.1177/1557988309335823.

[3] R. H. Salk, J. S. Hyde, and L. Y. Abramson, “Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms.,” Psychol. Bull., vol. 143, no. 8, pp. 783–822, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1037/bul0000102.

[4] D. Belle and J. Doucet, “Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women.,” 2003, Blackwell Publishing, Belle, Deborah: Dept of Psychology, Boston U, 64 Cummington Street, Boston, MA, US, 02215, [email protected]. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00090.

[5] J. Platt, S. Prins, L. Bates, and K. Keyes, “Unequal depression for equal work? How the wage gap explains gendered disparities in mood disorders.,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 149, pp. 1–8, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.056.

[6] N. N. Maserejian, C. L. Link, K. L. Lutfey, L. D. Marceau, and J. B. McKinlay, “Disparities in Physicians’ Interpretations of Heart Disease Symptoms by Patient Gender: Results of a Video Vignette Factorial Experiment,” J. Women’s Heal., vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 1661–1667, Sep. 2009, doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1007.

[7] W. Häuser and M.-A. Fitzcharles, “Facts and myths pertaining to fibromyalgia.,” Dialogues Clin. Neurosci., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 53–62, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/whauser.

[8] J. P. Griffith and F. A. Zarrouf, “A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don’t assume it’s depression.,” Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 120–128, 2008, doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0206.

[9] S. P. Nuguru, S. Rachakonda, S. Sripathi, M. I. Khan, N. Patel, and R. T. Meda, “Hypothyroidism and Depression: A Narrative Review.,” Cureus, vol. 14, no. 8, p. e28201, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.7759/cureus.28201.

[10] S. Moideen Sheriff, G. Singh, N. K. Chukwunyelu, C. J. Ezeafulukwe, and O. A. Hassan, “Hyperthyroidism Masquerading as an Anxiety Disorder: A Report on a Misdiagnosed Case.,” Cureus, vol. 15, no. 8, p. e44071, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.7759/cureus.44071.

[11] M. Zielińska, E. Łuszczki, and K. Dereń, “Dietary Nutrient Deficiencies and Risk of Depression (Review Article 2018-2023).,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 11, May 2023, doi: 10.3390/nu15112433.

[12] W. K. Kim, D. Shin, and W. O. Song, “Depression and Its Comorbid Conditions More Serious in Women than in Men in the United States.,” J. Womens. Health (Larchmt)., vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 978–985, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4919.

[13] T. Singh and K. Williams, “Atypical depression.,” Psychiatry (Edgmont)., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 33–39, Apr. 2006.

[14] A. Barkil-Oteo, “Collaborative care for depression in primary care: how psychiatry could ‘troubleshoot’ current treatments and practices.,” Yale J. Biol. Med., vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 139–146, Jun. 2013.

[15] J. J. Sramek, M. F. Murphy, and N. R. Cutler, “Sex differences in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression.,” Dialogues Clin. Neurosci., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 447–457, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.4/ncutler.

[16] M. Courchesne et al., “Gender Differences in Pharmacokinetics: A Perspective on Contrast Agents,” ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 8–17, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.3c00116.

[17] K. G. Tesfamicael et al., “Efficacy and safety of pharmacogenomic-guided antidepressant prescribing in patients with depression: an umbrella review and updated meta-analysis,” Front. Psychiatry, vol. Volume 15, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1276410

[18] C. Y. W. Chan, B. Y. Chua, M. Subramaniam, E. L. K. Suen, and J. Lee, “Clinicians’ perceptions of pharmacogenomics use in psychiatry.,” Pharmacogenomics, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 531–538, Apr. 2017, doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0164.

[19] J. L. Havlik, S. Wahid, K. M. Teopiz, R. S. McIntyre, J. H. Krystal, and T. G. Rhee, “Recent Advances in the Treatment of Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Narrative Review of Literature Published from 2018 to 2023.,” Curr. Psychiatry Rep., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 176–213, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s11920-024-01494-4.

[20] P. Greenberg et al., “The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2019).,” Adv. Ther., vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 4460–4479, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02622-x.